ISEA Menu | Roman's Main Menu | Home | Search | Contact

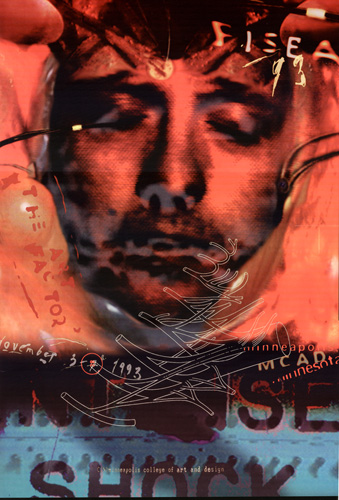

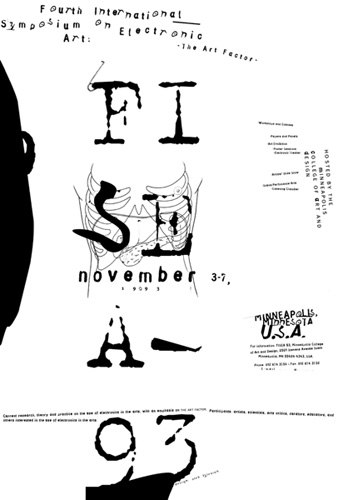

Fourth International Symposium on Electronic Art:

the art

factor This introduction was first published in the catalogue of ISEA 93 known then as FISEA ’93 . This introduction attempts to clarify why I led this symposium to focus on the “art factor”. This version was later published in Leonardo as an introduction to selected 1993 ISEA papers. (Leonardo 28:4, 1995, pp 285 ff). Introduction By way of introducing these papers [1] from the Fourth International Symposium on Electronic Art [2], I would like to say a few words about the term "electronic art" and about the theme of the Minneapolis symposium, "The Art Factor". In planning the "call for participation" our program committee was forced to ask very specifically, "How do we define "electronic art"? In seeking an answer the committee saw a need to identify relationships between emerging electronic technology and arts traditions. Some felt that technological achievement placed in an arts context as "art" should be subjected to critical assessment as "art", perhaps more so than discussion of the technology. A symposium focused on "the art factor" could open doors to the critical basis for distinguishing between "art" and the technologies employed for creating that art. Electronic Art Recently a colleague called the term "electronic art" an oxymoron. By this I believe she meant a self-contradictory term. Several years ago when we contemplated this symposium I too questioned the use of the term "electronic art," as did our committees and many others. But no longer. The use of changing technologies in the practice of art has been an on-going phenomenon. The work of pioneering artists has not been easily recognized or fairly assessed. The medieval scriptorium included artists who practiced the art of "calligraphy," which produced great masterpieces such as the Book of Kells. The advent of printing brought the art of "typography," which changed the art of the book as radically as the technology of printing changed Western culture. Yet how many contemporaries of Aldus Manutius (1449--1515) perceived or understood during the early years of the Aldine Press (from, say, 1495 to 1500) the immense impact the press would have? How many humanists at the turn of the sixteenth century failed to see that standardized movable type would alter the role of the artist's hand in both the design and production of the book? Are we not at a similar crossroads today? Since World War II, electronics has achieved radically new capabilities and has attracted hundreds of artists to experiment with its use. There are more than 1800 entries in the 1993 edition of the International Directory of Electronic Art. Although reference to electronic music dates back to as early as the sine-wave tones of Leon Theremin in 1924, it was the perfection of the tape recorder in the 1940s that thrust electronic music forward. Referring to the arts in general, the term "electronic" has been in substantial use for several decades, with a pronounced presence since the founding of Ars Electronica in 1979 at Linz, Austria. What is the post--WW II technology in electronics? It is the integrated circuit that makes the use of logic circuitry practical for almost any application---from automobile cruise control to automated bread-making. Today's electronic controllers exhibit uncanny abilities and a semblance of "intelligence," including simulating the human voice and controlling vast networks of information. Can we identify aesthetic issues associated with the use of these "controllers" in the arts---controllers with seemingly intelligent behavior? Their use raises questions associated with authorship and the "hand" of the artist. One radical aesthetic challenge results from the use of "genetic algorithms" and "cellular automata" in art, which some artists and musicians are using to "breed" forms (e.g. Biogenesis by William Latham, U.K., FISEA 93 Electronic Theater; and the work of Eduardo Miranda, CAMUS [Cellular Automata Music], FISEA 93 presenter). Who (or what) is in charge? Most FISEA 93 presenters, including authors of the papers in this special section, are artists whose work is radically "in-formed" by electronic procedures---work that may clearly be called "electronic." Others have collaborated with artists as electronic toolmakers. Some of these artists have wrestled with the giant for many years, prodding it to serve their artistic vision. To the earlier question, then, "Is electronic art an oxymoron?" we must say emphatically "no!"---not any more so than the terms "graphic art," "stained glass art," or "film art." The Art Factor In "electronic art" exhibits, we often see brilliant technology. But brilliant technology without "art" may be likened to a body without mind and soul---a floundering entity or a corpse. From the beginning, the FISEA 93 Program Committee, recognizing that the clamor of new technologies too easily takes center stage, centered its interest on artistic procedures and information processing by artists. For this reason they chose to focus the Minneapolis symposium on "the art factor." The symposium's call for participation identified the need for dialogue focused on the emerging artist-machine dialectic from the perspective of art criticism. This new cultural frontier has been changing the way we experience and interact with our world. Clearly, our machine culture will come to maturity by cultivating, celebrating and integrating "art," both intentionally and qualitatively. The artistic work of the cyber culture manifests itself as a new edge preceding any art theory or criticism about itself. For this reason we saw a need to draw those involved with this new edge into a more focused sharing and discussion of their "art," both in theory and in practice. So FISEA 93 was orchestrated to foster dialogue about the "art factor," especially for those younger artists who have grown up more with joysticks than with paint brushes. The intention has been to promote a greater understanding of both the formal aspects of the work and its technology. In keeping with our theme, the call for participation explicitly invited work that submitters considered being "art," thus providing ground for the committees to discover the art factor through the window of submissions. Why did we want to focus strongly on the critical language and the criteria we use for the "art" of machine culture? We did so because our relationships with each other, the world and the things we make are being radically transformed as "ubiquitous computing" invades our lives. This radical transformation includes serious changes in how we create and talk about cybernetic art. From the use of networks and form generators to genetic algorithms and computer viruses, we see artists using technologies that challenge assumptions about original art, individual style and private expression. In some instances the procedures are entirely executed from coded procedures. Shall we call this art? While the "modern" dogma has served its time well, its critical language and assumptions pertain to a passing culture in which cybernetics was the stuff of science fiction. The "modern movements," like fashion, were in dialectic with their predecessors---"art on art," as it were. But those artists who have pioneered the stuff of cybernetics have come to us somewhat sideways, intensely involved with the interaction between humans and machines. The whole range---from networks to artificial life- --has seduced many to total commitment. This includes a growing number who come directly out of the sciences and cross over to the world of art. What draws them? How are we to assess their work? The artists' statements and works in the Minneapolis show, and the papers published here, provide a ground for wrestling with these problems. From its inception in 1988, ISEA has been evolving terminology and formal categories for reviewing and exhibiting multifaceted art forms---cyber art, electronic art, computer art, digital media. Every ISEA symposium has two things in common---a commitment to the arts and serious involvement with the use of an electronic technology. ISEA Voices The selection and publication of ISEA papers by Leonardo began with the first ISEA symposium in Utrecht in 1988; this relationship with Leonardo brings the annual ISEA dialogue to a larger audience. ISEA's published documents provide only a hint of an intense week of workshops, poster sessions, exhibitions and papers. These ISEA events are both the fruit and the stimulus for those with the common interest of coming together to share their visions, problems and aspirations. Many attendees of the first ISEA symposium in 1988 discovered others traversing a similar path. Always, the shape of these symposia is defined by the participants---not just those who present papers or exhibit, but also all who submit works or take part in the discussions, both public and private. Juries and committees make it possible to come together in a meaningful way, but those who participate create the substance and meaning of the symposium as it unfolds and prepares ground for the next. So the process yielded one ambiance in Sidney (1992), another in Minneapolis (1993) and yet another in Helsinki (1994). For those who wish to join the dialogue, the ISEA symposia will continue in Montreal (1995), Rotterdam (1996), and Chicago (1997). On behalf of all ISEA participants, I extend my gratitude to Leonardo for being a friend to the ISEA series and for publishing our announcements and selected papers. Roman Verostko, Minneapolis, 1993 Notes 1. These introductory notes are based on those that appeared in the FISEA 93 Papers volume and the FISEA 93 Catalogue, which were distributed at the Fourth International Symposium on Electronic Art in Minneapolis. 2. ISEA is the acronym for the Inter-Society for Electronic Art, which gives the site approval each year for the International Symposium on Electronic Art. Up until 1994, meeting biannually, the symposium acronym included the letter of the series number thus: FISEA (First, Utrecht, 1988); SISEA (Second, Groningen, 1990); TISEA (Third, Sidney, 1992); and FISEA 93 (Fourth, Minneapolis). Beginning in 1994, the series dropped the first letter; thus: ISEA 94 (Helsinki); ISEA 95 (Montreal); ISEA 96 (Rotterdam); ISEA 97 (Chicago). ISEA 98 (Manchester-Liverpool, UK) UK); ISEA 2000 (Paris, France) Top of Page | ISEA Menu | Main Menu | Home | Search | Contact |

||||||